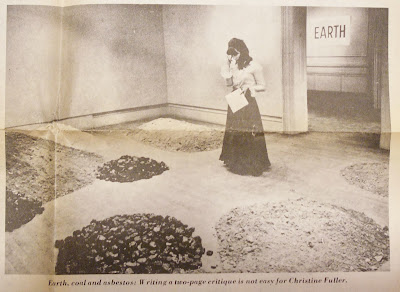

note: photographs by Peter Hujar (1934 - 1987)

In February 1981 I moved to New York City from the metropolitan Detroit area. I was 21 years old. Also, I did not drive.

Years after the fact when I consider what might have been if I had stayed in Detroit I assume it would have been the same boredom I now recollect dimly, the same lack of stimulation - no art, no books, no film. Of course there was some, but on a limited scale & for one with no automobility, it could be inaccessible. & considering all the "dumb jobs" one could get in NYC, there was no comparable economy in the shrinking Midwest. I worked at one point at a used bookstore in Royal Oak on Woodward Ave near 13 1/2 Mile - the shop manager at one point told me (this may have been when she laid me off), "

Go to New York - there's nothing here for you - you don't belong here." New York was considered highly dangerous for the most part, but open in ways that one wouldn't find in the duller & homogenous Midwest.

"Not belonging here" was also partial code for being gay - something I would understand with more depth, later. While there are environments much worse than Detroit for being gay, my own yearnings informed a sense that it could be better, somewhere else probably, probably meaning NYC. & it retrospect, it was.

By the time I arrived in NYC there was already a sense that whatever it was had ended already. The tawdry excesses of the 1970s were on the wane. For those who follow real estate in NYC, one of the curious unintentional documents of the 1970s is in the movie Saturday Night Fever, in particular the character Stephanie Mangano who becomes John Travolta's dance partner - she breaks out of the stasis of their Staten Island neighborhood to make a psychic leap to a grim studio apartment in the Upper West Side. Years afterwards when I hear people complain about "

the people who've occupied rent controlled apartments FOREVER" as if this is the cause for the absurd rents in NYC, her unhappy, restless, alienated character comes to mind.

Although it was only a few years later when I got to NYC, such mobility was on the wane, although as was said to me by the Michiganders I knew who preceded me to NYC at Columbia, Barnard & NYU, "

you can still find someplace."

The liberatory chaos of

Delirious New York manifested itself in many ways. By 1982 I lived in a shared apt on Stanton Street off of Essex, paying $200/month, & I worked part-time (which could often be overtime - it varied) at the Bleecker St Cinema. There was still a sense of NYC in general as dangerous, & within that a sense of "downtown" - of those who live either entirely below 14th St, or entirely above it. These boundaries now seem absurd - the 10013 zip code in Tribeca is now wealthier than 10021 (the former BUtterfield 8). But my youthful blitheness factored in, let's say downtown was still poorer, economically mixed, & bohemian.

By the time I began living and working downtown there had been sea-changes in the real estate potentials of SoHo, which had become a prosperous & centralized gallery district for contemporary art. Whether working at the Bleecker, which was 1 block north of Houston, or later, beginning in 1984, when I began to work at Film Forum, at that point on Watts St at the entrance to the Holland Tunnel, on the southwestern edge of SoHo, I spent the shank of my youth in the area, & its expanding galleries of the globalizing Art World. With its "success" the galleries moved elsewhere, replaced by high end boutiques, but that came later. In the 1980s there was still a texture of differences in the area. The cafeteria

Food was still open (although now when I see the Gordon Matta-Clark film of it, I realize I was never there in that earlier incarnation), there were still some small storefront businesses, and the old Italian neighborhood on Sullivan & Thompson Streets, with the local tavern

Milady's. Unlike Midtown or the Financial District (which had NO residents at the time - quite a place to bicycle in the dead of night), the buildings were not too high & there was more sunlight. There were streets of heavy traffic as well as smaller residential blocks. West Broadway had already transformed significantly from what is seen in the introductory NYC scenes of the film

The American Friend, which came out in 1977.

One of my memories, which seems more like fiction or fantasy, occurred in my first week in NYC, when one of my Ann Arbor friends, D, took me to a SoHo loft where we had coffee with Hannah Wilke, who I did not know of at all until several years ago - all I recall is her chewing gum art. How goofy, but one of the charms of being young & witless in such a setting is that such things can occur randomly.

Another more professional encounter was at the Bleecker St Cinema, where among other tasks, I did 16mm projection (non-union) in a small space there called the James Agee Room. One afternoon it was leased out to Louise Lawler, who did a NYC version of "A Movie Will Be Shown Without the Picture" - I projected (without the picture) the Paul Newman movie The Hustler, which is 134 minutes - something a projectionist would notice first & foremost. Again - I barely knew this from nothing.

Without any specific personal agency, the galleries were part of my everyday, which now seems incredible. Working at the Bleecker & then Film Forum & the short-lived VanDam (run by a short-lived distribution company which I suspect was a money laundering outfit) &

Anthology Film Archives, when it reopened on 2nd Avenue in 1988, I took it for granted, & it was the only time in my working life when lunchtime was genuinely interesting.

In the past 2 years, working with undergrads I've found the students are more informed with our hyper media saturated environment than us oldsters - or they think they are informed, & they think that it is theirs somehow. From my middle-aged perspective it seems entirely false & misleading, but I realize that I need to go against the same youthful impulses in myself, now a fading memory, in order to contend with the ideas brought up in the exhibit

This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s, curated by Helen Molesworth, at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago.

The catalog for the exhibit documents cultural upheavals in the US (primarily), using a time frame of 1979- 1992, and as conceptual markers, the impact of feminism in art practices followed by the impact of AIDS. The essays by the curator Helen Molesworth and Frazer Ward, Kobena Mercer, Johanna Burton, Elisabeth Lebovici, Bill Horrigan, and Sarah Schulman present multiple perspectives of the time, in themes titled The End is Near, Democracy, Gender Trouble, Desire & Longing. This is an extremely rich book about art & the time.

As much as coming from the misery of Detroit to the horny energy of NYC was a boon, the 1980s was a remarkably alienating time in terms of culture. I was in Ann Arbor when Ronald Reagan was elected: the University of Michigan radio station played Leslie Gore's

It's My Party on a loop for 24 hours. That is, it wasn't a party to be happy about any more.

Kobena Mercer writes:

The idea of a public space that is independent of commercial interests and separate from the state is one of the elementary building blocks of modernity. It is a concept that helped overthrow the absolutist monarchies of seventeenth-century Europe, and it was a precondition of the democratic revolutions of the eighteenth century. To say that the critical art of the 1980s lays bare the restructuring of public and private boundaries that took place in late-twentieth-century life is to suggest that it is only now, with some thirty years' distance, that some of the era's aesthetic tendencies begin to reveal their far-reaching political significance.

. . . In the late 1970s conservative forces took command of "the new" by winning popular consent for their vision of a future that would consign the welfare state to history. Back when the New Right really was new it took a leading or hegemonic role in the imaginative drive to push back the frontiers of perception by positioning itself as the agent of modernization capable of redressing the ongoing crises of industrial capitalism. Neoconservativism thus heralded a future based on consumerism, new technologies, finance capital, and a service economy - all of which were to be delivered by the privatization of almost everything, from housing to education to health, that defined "the public good" under the terms of the post 1945 consensus . . .it was precisely the generative agency of the intersecting forces clustered around the shifting borders of public and private life that gave rise to multiple lines of dissensus in 1980s art. . . 1980s art reveals the catalyzing antagonisms put into by by an emergent conception of multiple publics . . . (p. 135)

Mass media, as a condition of daily life, informs the art in question, which is seen as a break with an earlier heroic High Modernism which exempted itself from politics, whether it be the perceived in activism or in daily life. Helen Molesworth posits that this was the first generation of artists to grow up with television - itself highly mutable & expansive from the 1950s through the 1980s. The deregulation & privatization of Cable TV is brought up, & there is particularly ripe mention by Dara Birnbaum, quoting Manfredo Tafuri that "

television was the real architecture of the time." (p. 156).

This Will Have Been reinvests the art from the period outside its mercantile potential (or mercantile splendor - this is not a "best of" sort of collection) with an agency that addresses the Reaganite/Thatcherite retro-spasms of change that occurred in this period.

The last 2 essays, by Bill Horrigan (

A Backward Glance: Video in the 1980s), & Sarah Schulman (

Making Love Making Art: Living and Dying Performance in the 1980s), touch on that of which I know next to nothing - that is, the history of video; & one that which touches on something that I experienced as well - the highly mutable performance scene in the East Village, once upon a time. After reading the catalog I read Sarah Schulman's book The Gentrification of the Mind - in it she makes a comment that doing "performance" for a young artist is now synonymous with "private income" - whereas the performance she relates in the MCA catalog predates such a denotation. It's a lost world of "Whispers" on Sunday evenings at the

Pyramid Club, or Jennifer Miller the Bearded Lady, all highly extraordinary & accessible in an everyday world.

The Schulman essay is up front about varying incomes, capricious real estate, & porous emotional and sexual liaisons: She also suggests some of the joy of being young & relatively carefree, in a partially collapsed city. As an addendum, I would also recommend another project Sarah & Jim Hubbard put together, the

ACT UP Oral History Project.

I found the 1980s to be an intensely alienating time. Competitive class differences became marks of distinction, from the top down. Any wayward bohemian dalliance with art was superseded by a hierarchy of professionalized practitioners. With the spread of HIV and AIDS a Foucauldian paranoia of a harsh indifferent Administration (that is, multiple administrations of power) became very real and did its best to remain immovable except under the duress of insistent, dedicated activists. In terms of real estate speculation, the city became a violent machine of gentrification which has driven so many out with a hostile economic logic, for greener but not necessarily better pastures. In the abstract I tend to think of it as a kind of Hell - there is a recoupment in all these sources which gives me a plateau to think otherwise.